Modern day Laos was once known as the Kingdom of Lan Xang, the Kingdom of a Million Elephants. Its founding goes back to King Fa Ngum in 1353 but it reached the zenith of its power in the sixteenth century. During a period of about fifty years three kings extended the power of Lan Xang to reach over all of modern day Laos and Northern Thailand. During this time these kings promoted Buddhist culture and built some of the most important Buddhist temples and stupas in Laos, sites which today are still highly revered by the Lao people whilst being promoted as major tourist attractions. In this article we visit five of these magnificent Buddhist sites and explain their place in Lao history.

Vat Visounarath

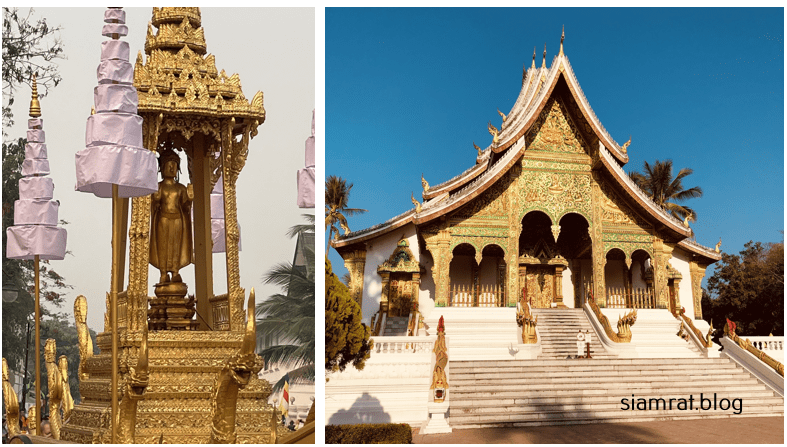

We start our journey at the oldest operating temple in Laos, Luang Prabang’s Vat Visounarath named after Lan Xang’s King Visounarath (r.1500-1520). King Visounarath was a devout Buddhist and on ascending to the Lan Xang throne he arranged for the Prabang Buddha image to be bought from Vientiane to Luang Prabang (At that time know as Xieng Dong Xieng Thong). The Prabang, a buddha image in the “dispelling of fear” posture, is made from a gold, silver and bronze alloy and weighs about 50kg. It is said to have originated in Sri Lanka and it was King Visounarath who established it as the palladium of his kingdom, a position it still holds today in modern Laos.

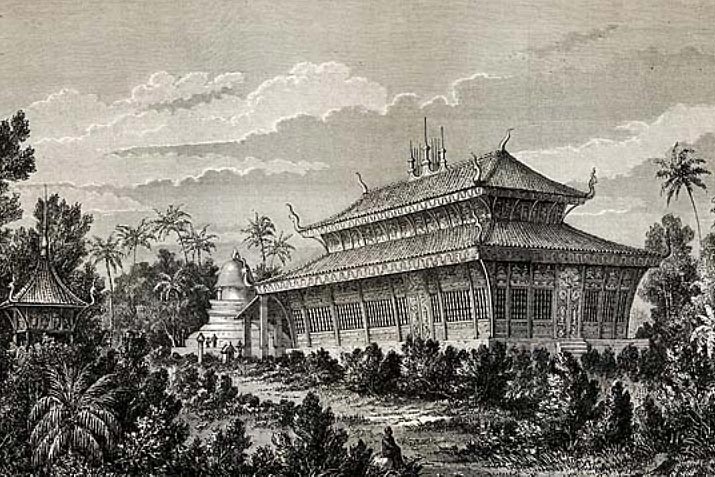

To house this most sacred of Buddhist icons King Visounarath ordered the construction of the Great Viharn of Vat Visounarath. This huge temple had a double roof supported by twelve huge teak pillars about 30m in height which had been taken from all the forests of the kingdom, each bearing an individual name. The temple walls sloped slightly outwards and the windows and eaves were covered with intricately carved ornamentation, supposedly to resemble a traditional funeral casket, thus reminding people of the impermanence of life.

Sadly the magnificent Great Viharn of Vat Visounarath is known to us now only through a drawing made by the French artist and explorer Louis Delaporte who visited Luang Prabang in 1867 as a member of the Mekong Exploration Commission. Twenty years later Luang Prabang was sacked by Chinese bandits known as The Haw. Most of the town was burnt to the ground, including Vat Visounarath. Luckily the Prabang Buddha was saved and today it resides in the Haw Prabang, built in the 1960’s, in front of Luang Prabang’s old royal palace.

Vat Visounarath was rebuilt by the French colonial authorities between 1896 and 1898. Although reconstructed with brick and plaster an attempt was made to recapture the appearance of the original Great Viharn. In the 1930’s the temple was used by Prince Phetsarath as a museum for religious artefacts that he collected on his travels around Laos.

Today the temple is still in use whilst charging a small entry fee to tourists. It is well worth a visit to see not only the temple building but also the massive Buddha image Pha Luang and the dozens of old wooden Buddha images and other old artefacts around the walls of the temple. Look out for the beautifully carved wooden screen depicting a battle between the monkeys Hanuman and Nilaphat which was commissioned in 1915 by Chao Boun Khong, the Viceroy of Luang Prabang 1890 – 1920.

Vat Aham

Walking through a rather crooked stone gateway on the north side of Vat Visounarath we come to the smaller temple of Vat Aham (Temple of the Blossoming Heart) which was founded by King Visounarath’s son and heir King Phothisarath (r.1520-1548). Like his father King Phothisarath was a devout Buddhist. But he was determined to impose a much stricter interpretation of Buddhism onto the Lao and he set out to extinguish the Lao belief in animist spirits or phi. In 1527 he issued a decree banning spirit worship and many traditional practices throughout Lan Xang. About the same time he founded Vat Aham to inter the remains of his father King Visounarath. Its location was deliberately chosen as this was the ancient site of the spirit house for Luang Prabang’s founding spirits Phou Yeu and Ya Yeu (Grandfather and Grandmother Yeu). The new temple was built both to carry on the memory of the king’s father but also to eliminate the centre of animist spirit worship in the kingdom.

King Phothisarath enforced Theravada Buddhism as the centre of Lao cultural life a position it still holds strongly today. But equally his attempt to eliminate animism failed. Lao culture is still suffused with beliefs and practices concerning phi spirits of the land, water and trees. And nowhere is King Phothisarath’s failure on this matter more evident than at Vat Aham itself where every year during Lao New Year (mid-April) Luang Prabang’s founding guardian spirits Phou Yeu and Ya Yeu still come to life and play a central role in the Lao New Year ceremonies around Luang Prabang.

Vat Aham was originally the residence of the Pha Sangkhalat or Supreme Patriarch of Laos and was thus a temple of great importance in the kingdom. The current temple building at Vat Aham, in classic Luang Prabang style, dates to around 1818 during the reign of King Manthatourath (r.1817-1836). But it was in this same period that the residence of the Supreme Patriarch was moved to Luang Prabang’s newly renovated Vat Mai, thereby lowering the importance of Vat Aham.

Vat Xieng Thong

At the tip of Luang Prabang’s peninsular we find Vat Xieng Thong, the jewel in the crown of Lao’s thousands of temples. This magnificent example of Lao religious architecture was built by command of King Setthathirath, eldest son of King Phothisarath. Setthathirath came to the Lan Xang throne in 1548. Soon after King Bayinnaung became the ruler of Burma and embarked on an series of expansionist wars across the region. Lan Na, which Setthathirath himself ruled over until 1551, fell to the Burmese in 1556. Facing this expansionist threat from the Burmese Setthathirath decided to move the capital of Lan Xang south from Xieng Dong Xieng Thong to Vientiane. The move began around 1563 with Setthathirath offering up the area of his royal palace to build a new temple Vat Xieng Thong, Temple of the Golden City. It was also at this time that the name of the city was changed from Xieng Dong Xieng Thong to Luang Prabang, honouring it as the home of the sacred Lao talisman the Prabang.

Luckily Vat Xieng Thong was one of the few temples in the city to be spared destruction by the Chinese Haw in 1887 – their leader Deo Van Tri had once been a novice at the temple and he used the temple as his headquarters during the fateful weeks his forces occupied the city. The temple remained under royal patronage until the end of the monarchy in 1975. It is still a working temple with resident monks and for a small entrance fee visitors can admire this most famous of Lao temples with its cascading roofs sweeping down low towards the ground. The walls are decorated with gold on black stencils which inside depict the life of Luang Prabang’s legendary first king Chanthaphanith as well as Buddhihst Jataka stories. On the outside rear wall a beautiful mosaic depicts the tree of life, an art work that was added in the 1960’s by Lao artist Thao Sin Keo.

There are other important shrines in the temple grounds such as the Red Chapel that houses a bronze reclining Buddha image dating to 1569, the chapel of the Pha Man housing another highly revered Buddha image, and the Royal Funeral Carriage House that houses the carriage used in 1961 for the funeral of King Sisavangvong.

Vat Pha Keo

Next on our tour we must follow King Setthathirath’s foot steps south to Vientiane. King Setthathirath (r.1548-1571) had ascended to the Lan Xang throne whilst already ruling over Lan Na from Chiang Mai but to establish his authority over Lan Xang he moved back to Xieng Dong Xieng Thong. He bought with him the sacred Phra Keo Morakot that had been kept for nearly 80 years at Wat Chedi Luang in Chiang Mai. Fifteen years later when he relocated the Lan Xang capital to Vientiane he again carried with him this sacred Buddha image that is better known to tourists today as Thailand’s famous Emerald Buddha.

On arriving in Vientiane in the mid-1560’s Setthathirat had built the huge Vat Pha Keo as a suitable setting for the Phra Keo Morakot. Although built contemporaneously with Luang Prabang’s Vat Xieng Thong the architecture reflects the different regional styles with high multi-tiered roofs supported by twenty eight impressive columns and a surrounding terrace. Vat Pha Keo became King Settathirat’s personal chapel for worship and no monks resided there.

Unfortunately subsequent history was once again unkind to one of Lao’s most impressive temples. In 1779 Siamese forces from Bangkok, led by Chao Chakri (Later to become King Rama I), attacked Vientiane. Vat Pha Keo was destroyed and the Phra Keo Morakot was carried back to Bangkok where it still resides today, now the palladium of the Thai Kingdom. Vat Pha Keo was rebuilt during the reign of King Anouvong (r.1804-1828) only to be destroyed again by another Siamese attack in 1828 which totally annihilated Vientiane.

Some seventy years later when the French began to incorporate Lao territory into their Indochinese colony, Vientiane was little more than a village with impressive ruins buried in the jungle. Nevertheless the French understood the significance of this ancient city to the Lao and sought to rebuild it as the capital of their Lao possessions. In the 1940’s the French authorities under the auspices of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient began work to rebuild Vat Pra Keo. The Chief Engineer for this project was Prince Souvanna Phouma who two decades later would be Prime Minister of Laos. However, this reconstruction under the French made some major concessions to French colonial pride. Like all Buddhist temples Vat Pha Keo was built facing East to the rising sun. But the French reconstruction turned the temple around to face West so that its main entrance would face the official residence of the French Resident-Superior (Now the site of the Presidential Palace).

Vat Pha Keo ceased operating as a temple after 1975 and is now open to tourists as the museum Ho Pha Keo with many Lao and Khmer artefacts on display. The main Buddha image is Pha Chao Teu which is a bronze casting believed to have been made in Vientiane in 1783. Also of note are the intricately carved rear doors which have been preserved from the earlier ruins.

Pha That Luang

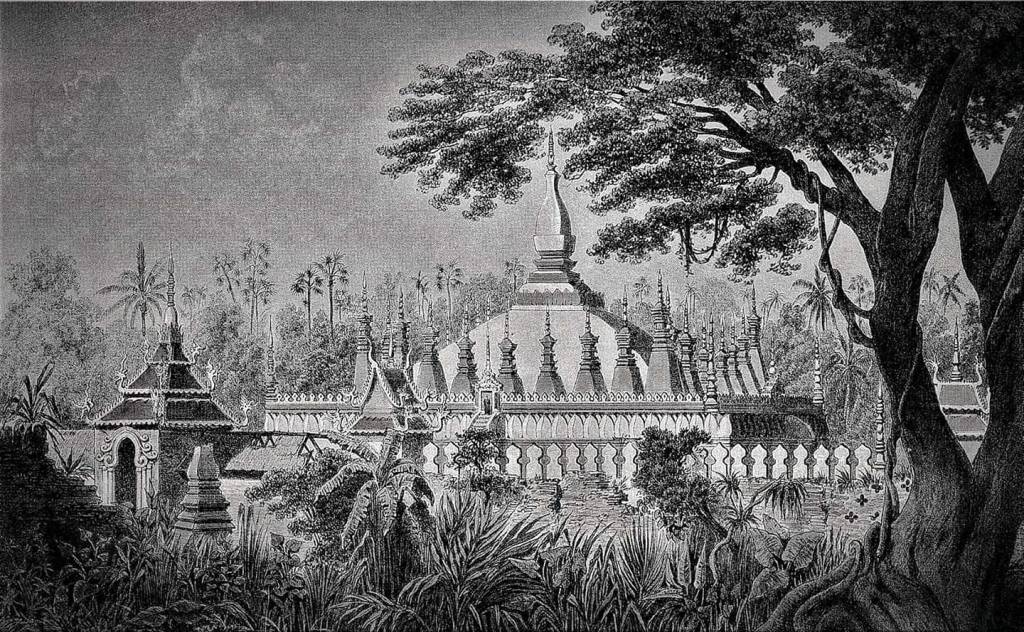

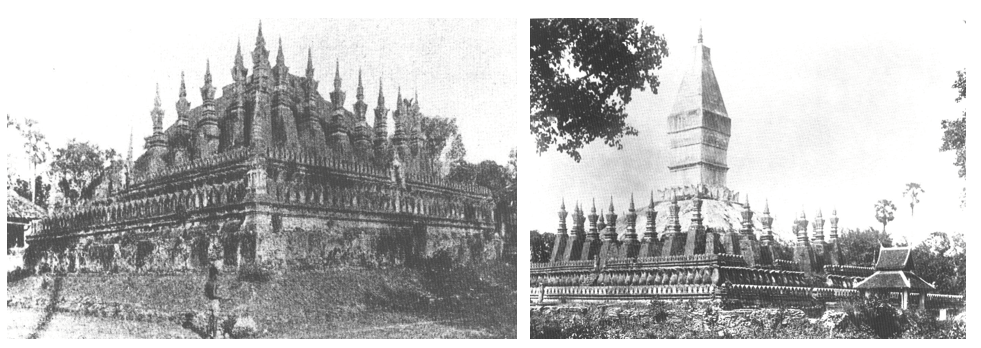

Our final stop is not a temple but is King Setthathirath’s other great architectural legacy, Pha That Luang, an enormous golden stupa north-east of the centre of Vientiane. This stupa was also constructed after the move to Vientiane in 1566. It was built on the site of much older Khmer ruins which in turn legend says were built on the site of a 3rd century B.C. stupa that contained the breast bone of the Buddha. In 1641 Gerrit van Wuysthoff of the Dutch East India Company became the first European to visit Vientiane where King Soulinga Vongsa received him with great ceremony at Pha That Luang. Wuysthoff described the supa as an “enormous pyramid and the top was covered with gold leaf weighing about a thousand pounds”.

Pha That Luang survived the Siamese invasions of 1779 and 1828 only to be destroyed by the Chinese Haw bandits in 1887 who sought the jewels and artefacts encased inside the stupa. In 1900 the French reconstructed the stupa but in a crude manner without reference to the original style. Fortunately another of the drawings by artist-explorer Louis Delaporte showed what the original stupa looked like and in the 1930’s the French restored the original graceful lines of the Pha That Luang.

Today Pha That Luang is the national emblem of Lao People’s Democratic Republic, being featured on bank notes and all government media and buildings. It is a major tourist attraction for the country but is also still a centre of worship for the Lao people, especially in November each year when it is at the centre of Vientiane’s largest festival.

Where to Go

Buy Me a Coffee

References

- Simms, Peter and Sanda. The Kingdoms of Laos. Six Hundred Years of History. Curzon Press. 1999.

- Holt, John Clifford. Spirits of the Place. Buddhism and Lao Religious Culture. University of Hawaii Press. 2009.

- Evans, Grant. The Last Century of Lao Royalty. A Documentary History. Silkworm books. 2009

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. Historical Dictionary of Laos. Scarecrow Press. 1992.

- https://www.luangprabang-laos.com

- https://www.orientalarchitecture.com/

marvelous! 2 2025 The Finest Fifty Years of Lao History Told Through Four Temples (And a Stupa) impressive

LikeLike